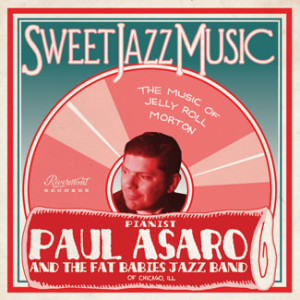

Paul Asaro’s ebullient stride-piano technique vividly

evokes an earlier era. You don’t encounter pre-bebop jazz

of this quality and commitment very often anymore.”

– Howard Reich of Chicago Tribune

About Stride Piano

Harlem Stride Piano developed out of the ragtime piano styles of New York City and the east coast, also known as “Eastern Ragtime”. The style continued the ragtime tradition of a march-like left hand see-sawing between a single bass note at the bottom of the keyboard, and a chord struck in the center of the keyboard. In general, ragtime pianists only stretched an octave or an octave and a half between the bass note and the chord in the middle but the stride pianists stretched much further towards the bottom end of the keyboard and the wider span give a much fuller sound. The syncopated figures in the right hand evolved into more varied and complicated patterns involving all manner of thirds, sixths, tenths, chromatic runs, broken chords, glissandos, and tremolo octaves. As it developed during the declining years of ragtime’s popularity and during the rise of the jazz age it further distinguished itself from ragtime piano in its sense of “swing” in the rhythm and its increasing use and the complexity of improvisation during perfomance. Stride piano was an east coast development and differed stylistically from the New Orleans jazz pianists such as Jelly Roll Morton in its voicings and melodic figures.

Harlem Stride Piano developed out of the ragtime piano styles of New York City and the east coast, also known as “Eastern Ragtime”. The style continued the ragtime tradition of a march-like left hand see-sawing between a single bass note at the bottom of the keyboard, and a chord struck in the center of the keyboard. In general, ragtime pianists only stretched an octave or an octave and a half between the bass note and the chord in the middle but the stride pianists stretched much further towards the bottom end of the keyboard and the wider span give a much fuller sound. The syncopated figures in the right hand evolved into more varied and complicated patterns involving all manner of thirds, sixths, tenths, chromatic runs, broken chords, glissandos, and tremolo octaves. As it developed during the declining years of ragtime’s popularity and during the rise of the jazz age it further distinguished itself from ragtime piano in its sense of “swing” in the rhythm and its increasing use and the complexity of improvisation during perfomance. Stride piano was an east coast development and differed stylistically from the New Orleans jazz pianists such as Jelly Roll Morton in its voicings and melodic figures.

Stride Piano, Pioneers and Developers:

James P. Johnson (1894-1955) Known as the “Father of the Stride Piano” and the “Dean of Jazz Pianists” Johnson was the most important innovator and pioneer of the stride style. He along with Jelly Roll Morton, were arguably the two most important pianists who bridged the ragtime and jazz eras, and the two most important catalysts in the evolution of ragtime piano into jazz. As such, he was a model for Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Art Tatum and his more famous pupil, Fats Waller. Johnson composed many hit tunes including “The Charleston”, the theme song of the Roaring Twenties, as well as”Old Fashioned Love” and “If I Could Be With You One Hour Tonight”. James P. remained the acknowledged king of New York jazz pianists until he was dethroned c. 1933 by the recently arrived Art Tatum, who is widely acknowledged by jazz critics as the most technically proficient jazz pianist of all time. Johnson began writing larger scale concert works in the late 1920s (“Yamekraw – A Negro Rhapsody”) and in the 1930s he turned his attention completely to symphonic forms producing works such as “Tone Poem” (1930), “Symphony Harlem” (1932), a symphonic version of W.C. Handy’s “St. Louis Blues” (1937), and the one-act opera “De Organizer” (1939), with lyrics by Langston Hughes. Although his symphonic works proved unpopular and were seldom performed Johnson’s influence and success are often overlooked, and as such, he has been referred to by Reed College musicologist David Schiff, as ” The Invisible Pianist ” and by biographer Scott E. Brown as “A Case Of Mistaken Identity”.

James P. Johnson (1894-1955) Known as the “Father of the Stride Piano” and the “Dean of Jazz Pianists” Johnson was the most important innovator and pioneer of the stride style. He along with Jelly Roll Morton, were arguably the two most important pianists who bridged the ragtime and jazz eras, and the two most important catalysts in the evolution of ragtime piano into jazz. As such, he was a model for Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Art Tatum and his more famous pupil, Fats Waller. Johnson composed many hit tunes including “The Charleston”, the theme song of the Roaring Twenties, as well as”Old Fashioned Love” and “If I Could Be With You One Hour Tonight”. James P. remained the acknowledged king of New York jazz pianists until he was dethroned c. 1933 by the recently arrived Art Tatum, who is widely acknowledged by jazz critics as the most technically proficient jazz pianist of all time. Johnson began writing larger scale concert works in the late 1920s (“Yamekraw – A Negro Rhapsody”) and in the 1930s he turned his attention completely to symphonic forms producing works such as “Tone Poem” (1930), “Symphony Harlem” (1932), a symphonic version of W.C. Handy’s “St. Louis Blues” (1937), and the one-act opera “De Organizer” (1939), with lyrics by Langston Hughes. Although his symphonic works proved unpopular and were seldom performed Johnson’s influence and success are often overlooked, and as such, he has been referred to by Reed College musicologist David Schiff, as ” The Invisible Pianist ” and by biographer Scott E. Brown as “A Case Of Mistaken Identity”.

Willie “The Lion” Smith (1893-1973) Full name: William Henry Joseph Bonaparte Bertholoff Smith. Born in Goshen, NY, “The Lion” is considered to be possibly the most original of the masters of the stride style, usually grouped together with James P. Johnson and Thomas “Fats” Waller as one of the three greatest practitioners of the genre. “The Lion” claimed to have earned his nickname as a gunner during World War I after volunteering to fire a French cannon in order to avoid being assigned as a sniper. “I shot those 75s at the Fritzies for forty-nine days without a break or any relief. Word got back about the several hits I had to my credit and a colonel came up and said, ‘Smith, you’re a lion with that gun.’ Before long everyone was calling me ‘Willie The Lion’, a name that has stuck with me ever since”. (from “Music On My Mind”, 1964) The Lion played on the first commercial blues recording, Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues”, in 1920, a record which kicked off the blues craze of the 1920s. Despite this success, Smith seldom recorded during the twenties and it wasn’t until 1935 that he began to record regularly under his own name beginning with a fine series of small band sides for Decca Records with a group called, “Willie The Lion Smith and his Cubs”. A definitive solo piano session for Commodore Records followed in 1939 featuring Smith playing both his own uniquely original compositions and his highly personal versions of various standards. The liner notes his 1958 LP “The Legend of Willie “The Lion” Smith” (Grand Awards Records GA 33-368) state: “Duke Ellington has never lost his awe of the Lion’s prowess.” It quotes Ellington as saying, “Willie The Lion was the greatest influence of all the great jazz piano players who have come along. He has a beat that stays in the mind.” Ellington demonstrated his admiration when composing and recording the highly regarded “Portrait of the Lion” in 1939. Orange County (NY) Executive Edward Diana issued a proclamation declaring September 18th Willie “The Lion” Smith Day in Orange County, the date of the first Goshen Jazz Festival.

Willie “The Lion” Smith (1893-1973) Full name: William Henry Joseph Bonaparte Bertholoff Smith. Born in Goshen, NY, “The Lion” is considered to be possibly the most original of the masters of the stride style, usually grouped together with James P. Johnson and Thomas “Fats” Waller as one of the three greatest practitioners of the genre. “The Lion” claimed to have earned his nickname as a gunner during World War I after volunteering to fire a French cannon in order to avoid being assigned as a sniper. “I shot those 75s at the Fritzies for forty-nine days without a break or any relief. Word got back about the several hits I had to my credit and a colonel came up and said, ‘Smith, you’re a lion with that gun.’ Before long everyone was calling me ‘Willie The Lion’, a name that has stuck with me ever since”. (from “Music On My Mind”, 1964) The Lion played on the first commercial blues recording, Mamie Smith’s “Crazy Blues”, in 1920, a record which kicked off the blues craze of the 1920s. Despite this success, Smith seldom recorded during the twenties and it wasn’t until 1935 that he began to record regularly under his own name beginning with a fine series of small band sides for Decca Records with a group called, “Willie The Lion Smith and his Cubs”. A definitive solo piano session for Commodore Records followed in 1939 featuring Smith playing both his own uniquely original compositions and his highly personal versions of various standards. The liner notes his 1958 LP “The Legend of Willie “The Lion” Smith” (Grand Awards Records GA 33-368) state: “Duke Ellington has never lost his awe of the Lion’s prowess.” It quotes Ellington as saying, “Willie The Lion was the greatest influence of all the great jazz piano players who have come along. He has a beat that stays in the mind.” Ellington demonstrated his admiration when composing and recording the highly regarded “Portrait of the Lion” in 1939. Orange County (NY) Executive Edward Diana issued a proclamation declaring September 18th Willie “The Lion” Smith Day in Orange County, the date of the first Goshen Jazz Festival.

Thomas “Fats” Waller (1904-1943) The most well known of the “Big Three” of stride piano, having been the prize pupil and later friend and colleague of the greatest of the stride pianists, James P. Johnson. Waller was one of the most popular performers of his era, finding critical and commercial success in his homeland and in Europe. He was also a prolific songwriter and many songs he wrote or co-wrote are still popular, such as “Honeysuckle Rose”, “Ain’t Misbehavin'”, “Squeeze Me”, “Keepin’ Out of Mischief Now”, “Blue Turning Grey Over You”, “I’ve Got a Feeling I’m Falling”, and “Jitterbug Waltz”. His composed stride piano display pieces include “Handful of Keys”, “Valentine Stomp”, and “Viper’s Drag”. Waller copyrighted over 400 tunes, many of which were co-written with the great lyricist Andy Razaf. Razaf described his partner as “the soul of melody… a man who made the piano sing… both big in body and in mind… known for his generosity… a bubbling bundle of joy”. Gene Sedric, a clarinetist who played with Waller on many of his 1930s recordings, recalls Waller’s recording technique with considerable admiration. “Fats was the most relaxed man I ever saw in a studio,” he said, “and so he made everybody else relaxed. After a balance had been taken, we’d just need one take to make a side, unless it was a kind of difficult number.”

Thomas “Fats” Waller (1904-1943) The most well known of the “Big Three” of stride piano, having been the prize pupil and later friend and colleague of the greatest of the stride pianists, James P. Johnson. Waller was one of the most popular performers of his era, finding critical and commercial success in his homeland and in Europe. He was also a prolific songwriter and many songs he wrote or co-wrote are still popular, such as “Honeysuckle Rose”, “Ain’t Misbehavin'”, “Squeeze Me”, “Keepin’ Out of Mischief Now”, “Blue Turning Grey Over You”, “I’ve Got a Feeling I’m Falling”, and “Jitterbug Waltz”. His composed stride piano display pieces include “Handful of Keys”, “Valentine Stomp”, and “Viper’s Drag”. Waller copyrighted over 400 tunes, many of which were co-written with the great lyricist Andy Razaf. Razaf described his partner as “the soul of melody… a man who made the piano sing… both big in body and in mind… known for his generosity… a bubbling bundle of joy”. Gene Sedric, a clarinetist who played with Waller on many of his 1930s recordings, recalls Waller’s recording technique with considerable admiration. “Fats was the most relaxed man I ever saw in a studio,” he said, “and so he made everybody else relaxed. After a balance had been taken, we’d just need one take to make a side, unless it was a kind of difficult number.”